The MDA Model: A Framework for Exceptional Game Design

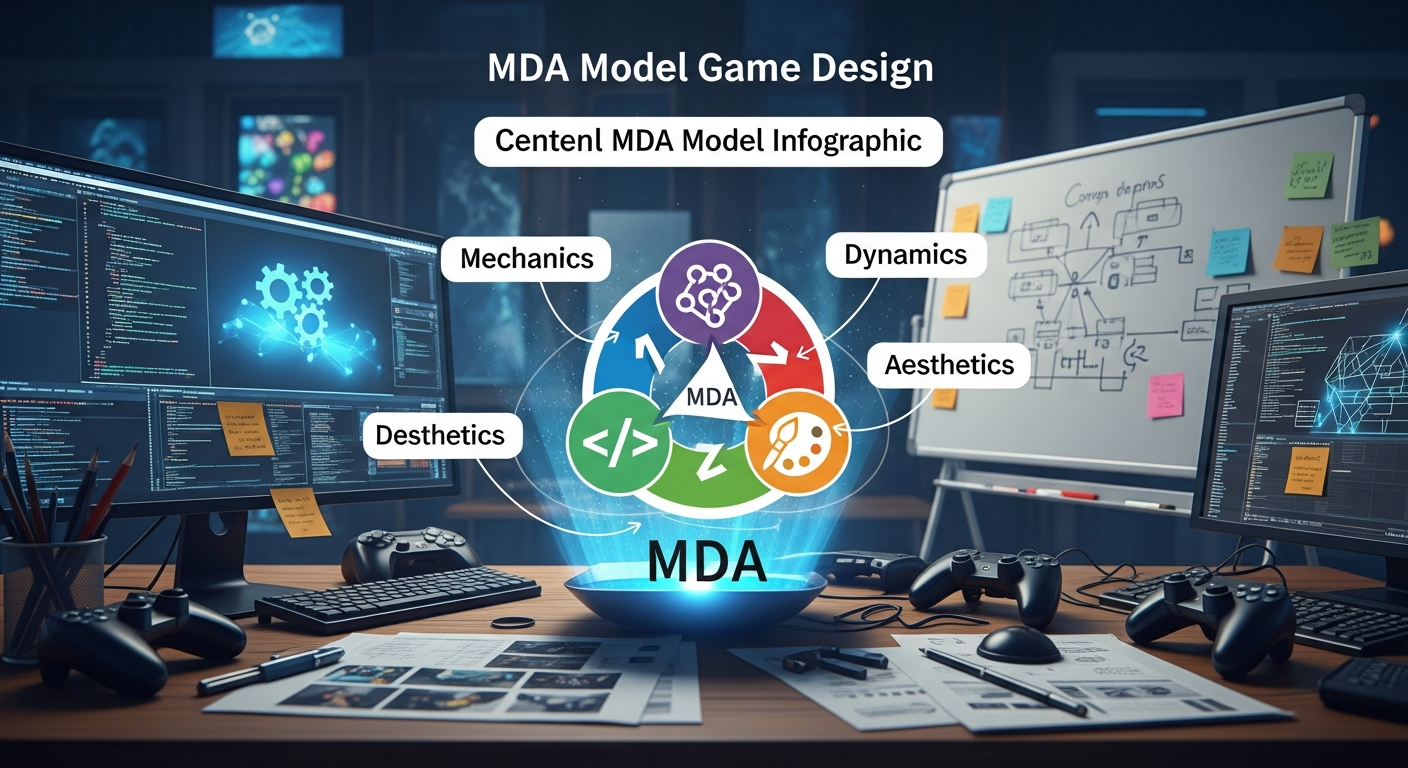

Game design is an intricate blend of art and science, demanding creativity, technical prowess, and a deep understanding of human psychology. While many designers create compelling experiences intuitively, a structured approach can elevate their craft, ensuring intent translates into tangible player enjoyment. Enter the MDA Model: Mechanics, Dynamics, and Aesthetics. This powerful framework, introduced by Robin Hunicke, Marc LeBlanc, and Robert Zubek, provides a lens through which designers can analyze, understand, and intentionally create games that resonate deeply with players.

In an era where engagement is paramount, whether in entertainment or education, understanding the fundamental components of an interactive experience is crucial. The MDA model offers a common language, bridging the gap between the game's intrinsic rules and the player's subjective experience. For anyone looking to build more engaging, intentional, and successful interactive products, from video games to MaxLearn Microlearning Platform modules, grasping MDA is a game-changer.

Deconstructing the Pillars: Mechanics, Dynamics, Aesthetics

The MDA model proposes that games can be understood by breaking them down into three distinct components, which flow in a specific direction from the designer's perspective to the player's experience. From the designer's viewpoint, the process typically starts with Mechanics, which then create Dynamics, ultimately leading to Aesthetics. Conversely, players primarily experience the Aesthetics, which are shaped by the Dynamics, themselves emerging from the underlying Mechanics.

1. Mechanics: The Building Blocks

Mechanics are the foundational elements of a game. They are the rules, systems, and data structures that define the game world and govern player actions. Think of them as the atoms and molecules of your game universe. These are the aspects a designer directly implements and controls.

- Rules: How players can interact with the game world and each other. (e.g., "move two spaces," "draw a card," "attack an enemy.")

- Actions: The verbs players can perform. (e.g., jump, shoot, build, trade.)

- Components: The static and dynamic elements of the game. (e.g., cards, dice, character stats, resources, victory conditions.)

- Algorithms: The underlying calculations and processes. (e.g., damage calculation, probability of an event.)

For example, in a chess game, the mechanics include the specific ways each piece moves (knight's L-shape, rook's straight line), the objective (checkmating the king), and the board layout. These are the concrete, explicit parts of the game. When designing an educational platform, the mechanics might include quiz formats, point systems, badges, or progress bars – all elements that contribute to a Gamified LMS.

2. Dynamics: The Emergent Play

Dynamics are the run-time behavior of the mechanics acting on other mechanics and on the player. They are not explicitly designed but rather emerge from the interaction of the mechanics and the players' strategies and decisions. Dynamics represent the "gameplay" itself, the flow and feel of the experience.

- Player Strategy: How players adapt to the rules and seek to win or achieve goals.

- Game Flow: The pacing, tension, and progression of the game session.

- System Behavior: How different mechanics interact and influence each other over time.

- Emergent Gameplay: Unanticipated but interesting interactions that arise from the rules.

Continuing the chess example, the dynamics emerge when players apply strategies like opening gambits, defensive formations, or aggressive attacks using the pieces' movement rules. The tension of a close game, the feeling of being outmaneuvered, or the satisfaction of a clever sacrifice are all dynamics. For a learning system, dynamics might involve learners competing on a leaderboard, collaborating on a project, or experiencing an Adaptive Learning path based on their performance, creating an individualized and evolving challenge.

3. Aesthetics: The Player Experience

Aesthetics are the emotional responses and experiences evoked in the player. They are the subjective feelings and interpretations that arise from playing the game. This is the "fun" factor, the ultimate goal of game design, and what the player perceives directly.

Hunicke, LeBlanc, and Zubek identified eight common aesthetic types:

- Sensation: Game as sense-pleasure (e.g., visual effects, tactile feedback).

- Fantasy: Game as make-believe (e.g., role-playing, immersive worlds).

- Narrative: Game as drama (e.g., story-driven games, character arcs).

- Challenge: Game as an obstacle course (e.g., puzzles, skill tests).

- Fellowship: Game as social framework (e.g., teamwork, competition, community).

- Discovery: Game as uncharted territory (e.g., exploration, hidden mechanics).

- Expression: Game as self-discovery (e.g., customization, creative tools).

- Submission: Game as pastime (e.g., repetitive tasks, mindless entertainment).

In chess, the aesthetics might include the intellectual challenge of outsmarting an opponent, the satisfaction of a well-executed plan (Discovery/Challenge), or the feeling of intense concentration (Sensation). For a powerful learning experience delivered by a MaxLearn Microlearning Platform, the aesthetics could be the sense of accomplishment after mastering a difficult concept, the joy of collaborative learning, or the narrative immersion in a simulated business challenge.

The Iterative Design Process with MDA

The true power of the MDA model lies in its application during the design process. Designers typically work backward from the player's experience:

- Start with Aesthetics: What kind of emotional experience or feeling do you want to evoke in the player? (e.g., "I want players to feel powerful and strategic," or "I want them to feel a sense of discovery and wonder.")

- Design Dynamics: Given the desired aesthetics, what emergent gameplay behaviors, player strategies, or game flows are necessary to create that feeling? (e.g., "To feel powerful, players need to be able to chain abilities effectively," or "To feel discovery, the world needs to hide secrets that reward exploration.")

- Implement Mechanics: What specific rules, actions, and game systems need to be put in place to support those dynamics? (e.g., "Abilities have cooldowns and combo bonuses," or "The map has branching paths and hidden passages.")

This is not a linear process, but an iterative loop. Designers will prototype mechanics, observe the resulting dynamics during playtesting, and then gauge if those dynamics are producing the desired aesthetics. If not, they iterate, adjusting mechanics or even re-evaluating the desired dynamics until the intended player experience is achieved. This iterative approach helps in identifying potential issues early on, mitigating the need for costly overhauls, and can even be seen as a form of Risk-focused Training for designers, allowing them to systematically address design flaws.

Benefits of Adopting the MDA Model

Incorporating the MDA model into your design philosophy offers several significant advantages:

- Clearer Communication: It provides a common vocabulary for discussing games, facilitating better collaboration between designers, developers, and even marketing teams.

- Intentional Design: Moves beyond accidental fun, enabling designers to consciously craft experiences rather than just hoping for positive outcomes.

- Targeted Problem Solving: When a game isn't working, MDA helps pinpoint the issue. Are the mechanics broken? Are the dynamics not emerging as intended? Or are the desired aesthetics simply not being felt by the players?

- Innovation: By focusing on the desired experience (aesthetics) first, designers are encouraged to think outside the box for unique mechanics and dynamics.

- Bridging Disciplines: It effectively translates developer-centric rules into player-centric experiences, making it valuable for interdisciplinary teams.

Applying MDA Beyond Traditional Games

The principles of MDA are not limited to entertainment games. They are profoundly relevant to any interactive experience where engagement and motivation are key, such as serious games, educational software, and corporate training. A MaxLearn Microlearning Platform, for instance, can leverage MDA to design highly effective learning modules.

- Mechanics: Interactive quizzes, simulated scenarios, peer-to-peer challenges, progress trackers, leaderboards, achievement badges. These can be easily created using an AI Powered Authoring Tool.

- Dynamics: Learners engaging in friendly competition, collaborating to solve a problem, adapting their study habits based on feedback, experiencing a sense of urgency in a simulated business environment.

- Aesthetics: The feeling of mastery after completing a difficult module (Challenge, Discovery), the satisfaction of helping a colleague (Fellowship), the immersive feeling of a realistic scenario (Fantasy, Narrative), or the sheer joy of learning something new.

By consciously designing for specific aesthetics, educational designers can craft learning experiences that are not only effective but also deeply motivating and enjoyable, leading to higher retention and application of knowledge.

Conclusion

The MDA Model is more than just a theoretical framework; it's a practical tool that empowers designers to create more thoughtful, engaging, and impactful interactive experiences. By systematically breaking down a game into its Mechanics, Dynamics, and Aesthetics, designers gain a powerful lens through which to understand the relationship between their creative intent and the player's subjective experience.

Whether you're crafting the next blockbuster video game, developing an innovative learning module for a MaxLearn Microlearning Platform, or designing a compelling gamified application, embracing the MDA model will enable you to move from intuitive design to intentional creation. It fosters a deeper understanding of what makes an experience truly captivating, ultimately leading to more successful and memorable designs that resonate profoundly with your audience.

.jpg)